Deeper Layers

Let’s move a layer deeper into planet Earth. The next layer in is called the cingulate cortex. We combine two ideas to understand what’s going on here. The deeper in you go, the closer you get to the emotions, what matters for the organism. And in terms of content, once more where you are is what you do. The cingulate cortex is a system that negotiates between the content of the cortex above and the emotions of the layer below.

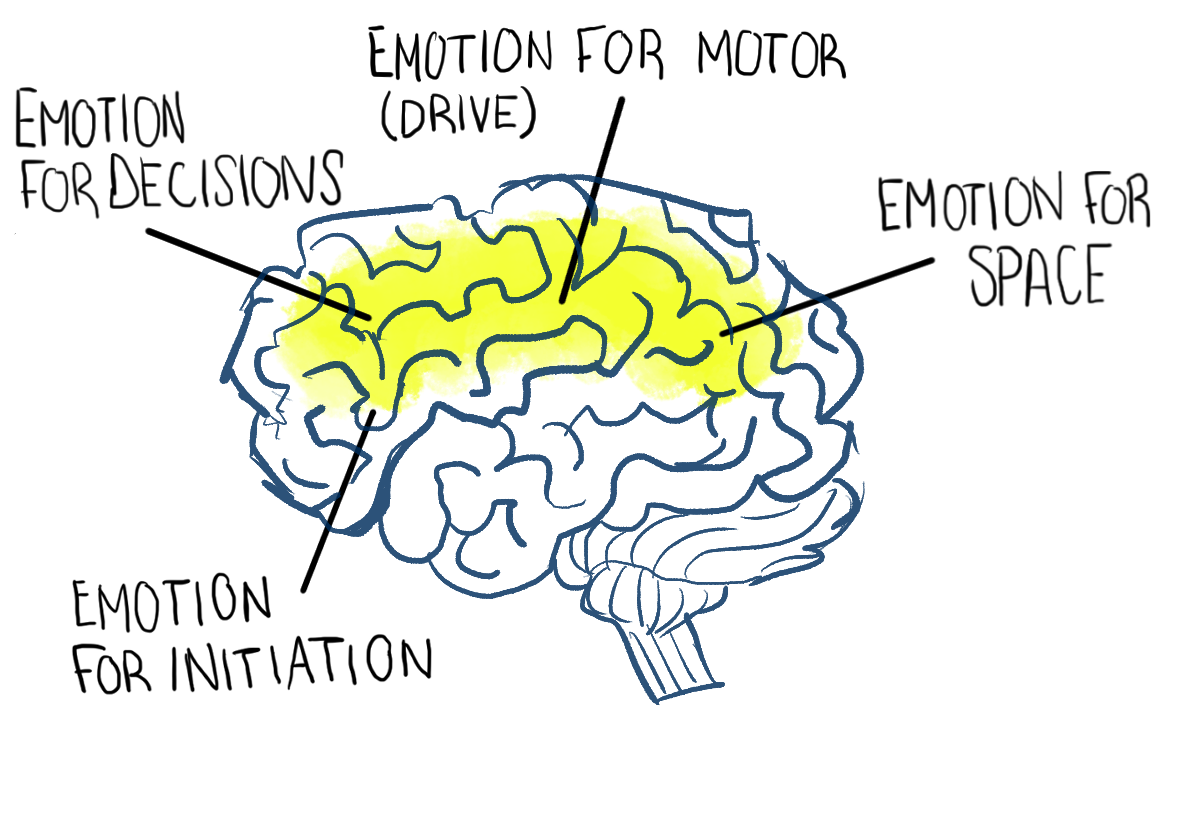

In the cingulate cortex, content is now more coloured by emotions and goals. Cingulate cortex under parietal cortex (processing space) will deal with emotions for space (sense of self in space). Cingulate cortex under motor cortex will deal with emotions for action (the drive to act). Cingulate cortex under frontal cortex will deal with emotions around decision-making and the initiation of behaviour (am I doing it right? is this fun?). However cold the processing of information is in the cortex, it simply cannot be separated from the emotional dimension that lies in the cingulate cortex underneath.

The next layer in combines a set of different structures, together called the limbic system. It’s the lava world of the emotions. Unlike the cortex, which is mainly the same across the sheet, the limbic system has a set of structures with specific functions. The set of structures are pretty similar across the primates. In fact, my neuroanatomist friend (see Introduction) said if someone gave him the limbic system of a human and a limbic system of a chimpanzee (casually, perhaps at a dinner party), he wouldn’t be able to tell the difference.

WARNING: BRAIN NAMES COMING UP. The structures in the limbic system are (roughly) the amygdala, the insula, the septum, the hippocampus, and the hypothalamus. Latin and Greek names again. Almonds, islands, partitions, seahorses, and below-the-bed, respectively. There’ll be a quiz on these later.

Here’s how to think about what’s going on. Emotions are the way that evolution has built long-term goals into the structure of the brain to give an organism the best chance of surviving and reproducing (two things evolution especially likes). The structures of the amygdala, insula, and septum are specialised for specific roles in emotion. For the amygdala, it’s about fear, aggression, whether to approach or avoid, to fight or fly or freeze. For the insula, it is about the bodily basis of emotion, what the body wants and what the body needs, the bodily self, feeling emotions in your guts. For the septum, it is about pleasure. These structures compete with each other for who is going to take control of the body, putting it in a state for whichever emotion wins. The structures compete to drive the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus in turn communicates with the distant bodily organs, by releasing chemical signals (called hormones) into the blood stream, putting the organs in the correct state to carry out different behaviours. 1

The hippocampus, by contrast, is a memory system, which brings together information from all the senses to create snapshot memories. The emotion structures can command the hippocampus to lay down strong memories. ‘Remember this situation, it’s important, it’s where we saw that scary spider!’

The idea that different parts of the limbic system deal with different emotions shouldn’t be taken too literally. Emotions are functions carried out by circuits, which involve detectors (of particular situations), modulation (of the activity of other brain regions, of the state of bodily organs), and memorisation (of experiences). Emotions themselves are sets of highly variable instances, which depend on the current situation, your own history of experiences, and your response. Fear may revolve around the amygdala as a threat detector, but fear isn’t just fear: you can tremble in fear, jump in fear, freeze in fear, scream in fear, gasp in fear, hide in fear, attack in fear, even laugh in the face of fear. 2

Lastly, the limbic system likes to talk to the front of the cortex. The frontal cortex provides the emotions with some context. The two systems are always chatting to each other. The limbic system might say, ‘Eeeek! A spider! Panic!’ and the front of the cortex might say, ‘Calm down. The spider you’re seeing is on TV. Should I change the channel for you?’

The conversation can go the other way. The front of the cortex, with time on its hands, might start to imagine the public speech that you have to give tomorrow and conjure up a nightmare of forgetting what to say. The limbic system hears this and plays along helpfully by setting the heart racing and stomach churning at the very thought of it.

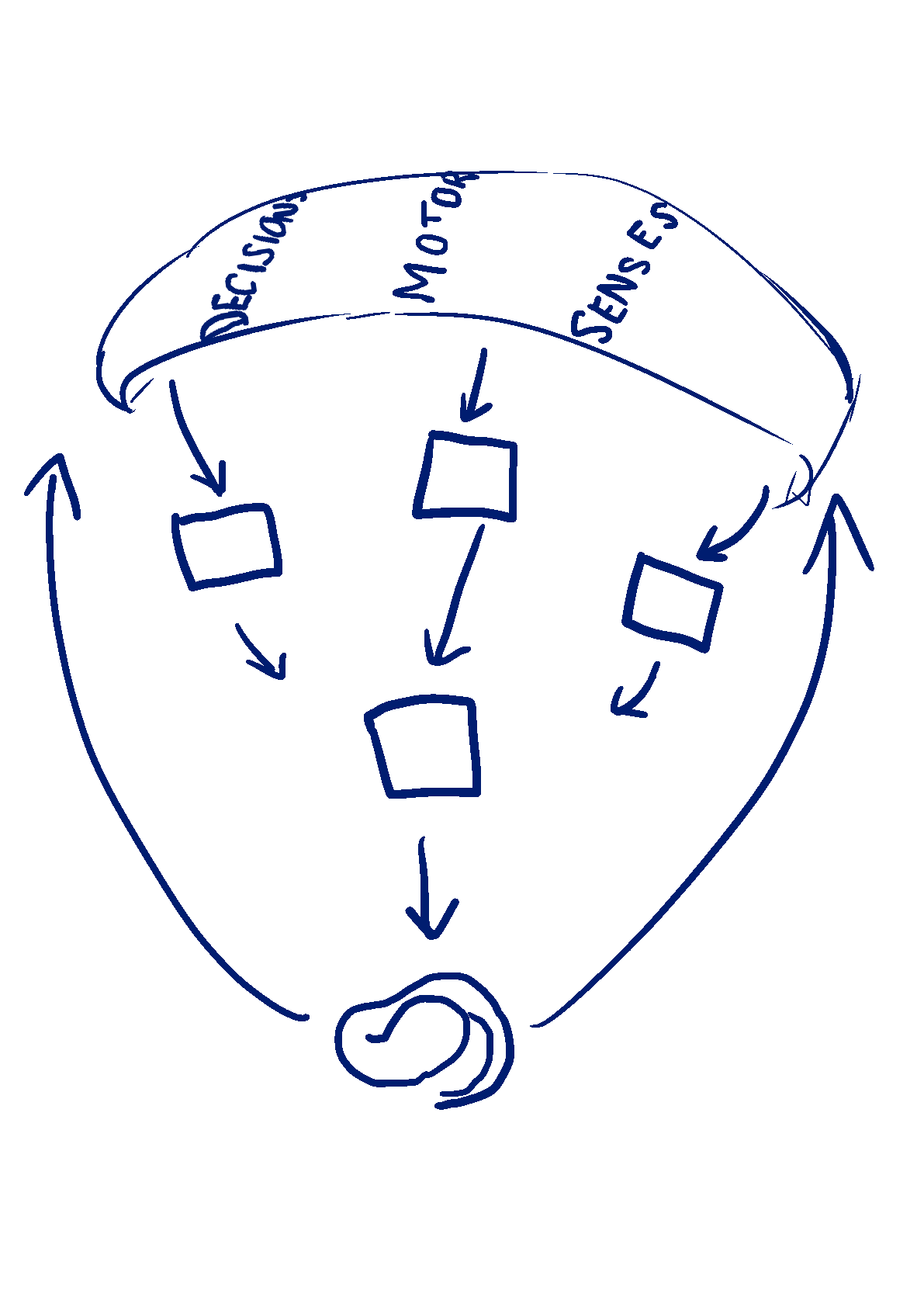

Okay, let’s go deeper, to the next layer down, to the basal ganglia. Up top, there are lots of parts of the brain competing to decide what to do. Look at this! Pick this up! Scratch your nose! Check your email! Smile at your neighbour!

At the bottom of the basal ganglia, there’s a structure called the striatum. It’s a stop-go system with looping connections to and from the cortex up above. What each loop processes depends on the cortex overhead. Again, where you are is what you do. The striatum decides what actually gets done: it’s the driver pressing the brake or the accelerator. Do an action or don’t do an action. Have a thought or don’t have a thought. Have an emotion, don’t have an emotion. The striatum decides. Its default is to leave the brake on, and only a winning signal will press the accelerator and drive a voluntary action. 3

Lastly, we reach the core of the planet. Here, we have the structures that relay basic sensory and motor information into and out of the brain (the thalamus), and structures that control basic functions like heart rate, breathing, sleeping, and eating (brain stem).

And I think that’s it. Oh wait, what’s this other thing here?

[1] Here’s how that might go: the amygdala wins the competition and tells the hypothalamus to get the body ready for fight or flight. Cells in the hypothalamus transmit a signal to the pituitary gland. The pituitary gland releases chemical messengers into the bloodstream. When the adrenal glands receive the signal, they respond by releasing adrenaline into the bloodstream. Organs across the body respond to the adrenaline. Heart rate goes up, increasing blood pressure; the air passages of the lungs expand, the pupils in the eyes enlarge, blood is redistributed to the muscles, and the body’s metabolism is altered to maximise blood glucose levels, mostly for the brain. Spiders, really, there’s nothing to be afraid of. Except the venomous ones, of course.

[2] See, e.g., Lisa Feldman Barrett, How Emotions Are Made (2017, Macmillan). [3] The striatum particularly uses a neurotransmitter called dopamine to oil its function (see later section on what neurotransmitters do). In Parkinson’s disease, the brain stops producing as much dopamine. The accelerator cannot be pushed, the brake is stuck on, and the brain struggles to produce voluntary / willed motor actions.